You have an amazing story, strong characters, and a plot that’s going to fast-track your career as a screenwriter. All that’s left is to format the final draft of your screenplay, which can take the fun right out of the process. A screenplay format template can help, but even then, it’s important to know the basics.

Let’s face it: Writing a screenplay from scratch is tough.

Even if you don’t count the creative aspect of the process, formatting alone can frustrate even the most experienced screenplay writers. However, if you know what you’re doing, at least you won’t make any mistakes and improve your odds of being picked up by a producer.

Whether you’re planning a short film, sitcom, or an internet show, keep reading. In this article, I’ll show you the ropes of screenplay writing by going over:

- The subtle difference between a script and a screenplay

- The 8 elements of screenplay writing

- The proper way to format a screenplay (and how a screenplay format template can help)

- How to write a screenplay

Let’s get started.

What is the Difference Between a Script and a Screenplay?

A lot of people use the terms “script” and “screenplay” interchangeably. While that’s not a major technical error that could affect the production, there is a subtle difference between both. A screenplay is a type of script, whereas not all scripts are screenplays.

To elaborate, here are two major ways to differentiate between both:

- Basic definition

- The way they’re formatted

Let’s take a look at what this means:

Basic Definitions

To elaborate, a screenplay is a type of script that is written for any visual performance that’s supposed to run on a screen, such as a TV show, movie, short film, or reenactment.

A script, on the other hand, can be for all of the things mentioned above, and more, including a stage play, a voiceover, a staged/fake interview, etc.

Note: A “spec script” is a screenplay that has been written but not commissioned or picked up/bought by a producer yet. When a spec script is refined and made more detailed for production, it becomes a “shooting script.”

Formatting

Another major way in which a typical script and a screenplay are different is the way they’re written (or formatted).

A scriptwriter typically only has to concern themselves with the chronology of the events, dialogues, and character names. It may also have other indicators, but there isn’t any universal roadmap or structure to follow when it comes to script formatting.

A screenplay writer, on the other hand, needs to properly format their work of art according to certain industry standards, in addition to the actual scriptwriting process. They need to specify the location and time, describe actions, and the transitions in between scenes, among other things.

This brings us to an important question:

Why Do Screenplays Need to be Formatted?

The reason why producers/filmmakers make such a big deal out of screenplay formatting is that it makes production extremely easier.

Knowing exactly how a particular scene is supposed to be shot, how dialogue is intended to be delivered, and the overall mood of the scene can really help in the preparation and direction of whatever the screenplay is for.

Everyone involved with the production – from the camera crew to the actors, and even those involved with editing – should be able to understand the vision the screenplay writer(s) had for each scene.

As an example, there are infinite ways (and moods) in which you can say the dialogue, “This is outrageous!”

A person reading the script should know the exact action and the mood associated with this line.

It could be an intense scene in a court of law, where a character who is wrongly charged with murder is being dragged away.

Or it could be a scene where a couple is out shopping and one of them is commenting at the price of an item while simply raising their eyebrow.

With proper use of screenplay elements (more on that below) and formatting, you can easily tell the difference.

What are the 8 Elements of Script Formatting?

Before you get to using a screenplay format template, it’s vital that you familiarize yourself with the basic elements.

These include the following:

1. Scene Heading/Slug Line

A scene heading (also known as a slug line) is exactly what it sounds like – a heading for the scene.

It tells the reader the exact place where a scene is supposed to take place. Additionally, it can also tell the reader about the time of day.

Consider it the most basic element of a screenplay.

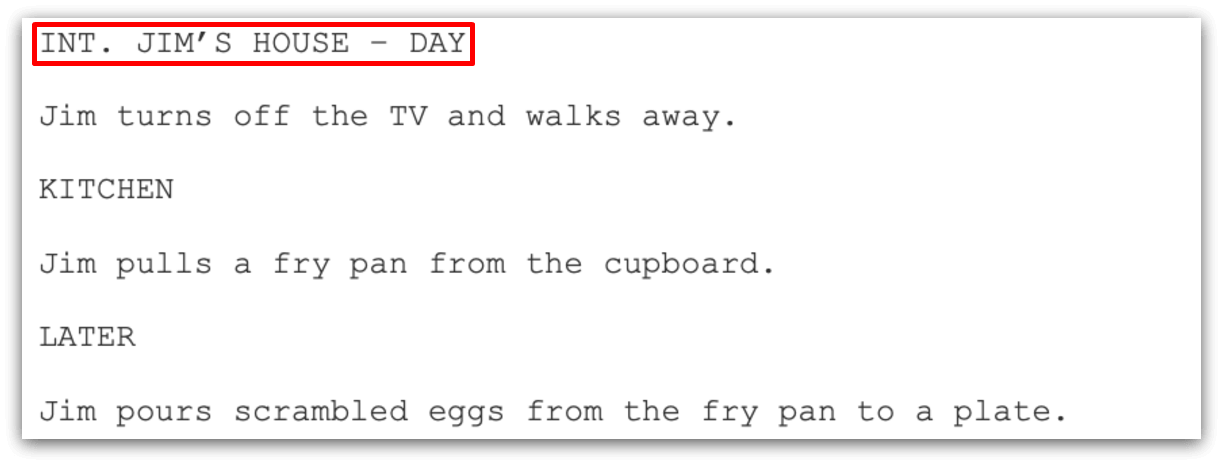

However, as simple as it might sound, there is a certain structure that you should follow. Here’s an example:

This includes the following elements:

- Place Indicator – these include Ext (“exterior” – for an outdoor scene) and Int (“interior” – for a scene taking place indoors). For scenes that take place in vehicles, use Ext/Int.

- Location Indicator – this should indicate the exact location where the scene takes place (i.e., a bedroom, kitchen, car, park, a café, etc.).

- Time – finally, specify the time of day. When referring to a flashback, some writers even mention the year.

Doing this for every scene might sound tedious, but it helps.

2. Action

A screenplay writer uses action lines (or descriptions) to describe how the character on a screen is supposed to act out a scene.

It’s what forms the basic foundation of the screenplay and essentially takes the play forward.

You can write action lines as regular sentences (there isn’t any specific structure to follow).

A few examples include:

- Sally walks in her warm office and takes her jacket off.

- The boys are having a night out at the local bar.

- It’s raining outside. Leo opens his eyes and finds himself tied to a chair. The creepy room is briefly lit up by a flash of lightning.

These action lines can be as descriptive as possible. Furthermore, they’re not intended to always merely describe what the characters are doing. As you can tell by the third example above, you can also use action lines to set the overall mood or the atmosphere of the scene.

3. Character Name

These don’t need any explanation.

When writing in action lines, they can go anywhere and are used as standard nouns.

However, when specifying who the speaker is, they go at the top and are indented towards the left (more on that later).

4. Dialogue

A dialogue is what a character is supposed to say during a scene.

Dialogues are the main element of a script. In most cases, they are the only element besides the names of the characters.

Dialogues are placed immediately beneath the names of their speakers or the parentheticals (if available).

Fun Fact: A screenplay doesn’t necessarily need to have spoken dialogue. There are several successful screenplays in which the characters don’t speak anything.

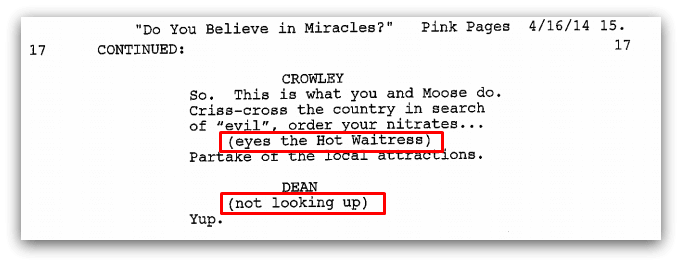

5. Parenthetical

An action describes what the characters are doing and the atmosphere of the scene.

A parenthetical describes how a character is supposed to say a dialogue and/or what they’re supposed to do (no matter how subtle) as they are delivering said dialogue.

Parentheticals are written in parenthesis (hence, the name), and can either come right after the speaker’s name or in-between dialogues if required.

Here are some more examples:

- (angrily)

- (whispering)

- (rolling her eyes)

- (looking

- (tearing up)

- (laughing)

Parentheticals help the actors deliver their dialogues exactly how the writer(s) envisioned while writing the script.

That is what makes them one of the most important elements of a screenplay format template, as they can make or break entire scenes.

6. Extensions

Extensions help in specifying how the character or the actor is supposed to record their dialogue.

Don’t confuse this with parentheticals, as extensions don’t indicate the way a dialogue is supposed to be read.

Instead, they indicate the visibility of the character when they’re speaking the dialogue. There are only 2 scenarios where they are used. Here are the technical terms used for them:

- O.S. – stands for “off-screen.” They are used when the character has to speak a dialogue when they’re not visible. They can be behind a closed door, hiding under a table, or just shouting from another room.

- V.S. – this means “voice-over.” This indicates that the character isn’t physically present in the scene, and could be narrating something, speaking on the phone, etc.

An extension is placed right next to the character’s name on the same line.

7. Transition

Transitions are instructions for the editing professionals about how to move or change over from one scene to another.

Over the years, as editing software became more advanced, screenplay writers got more options.

Some of the most commonly-used transitions include:

- Fade in/Fade out

- Cut to

- Dissolve to

- Flash cut to

- Iris in/Iris out

There is a popular opinion that screenplay writers shouldn’t use transitions and leave that up to the actual production team. However, it’s not a rule.

8. Shot

Finally, a shot is used to indicate a change in location within the same location specified in the scene heading.

For instance, consider a scene being taken place during daytime inside a character’s house whose name is “XYZ.” This is what the scene heading/slug line would look like:

Int. XYZ’s House — Day

If the character starts walking and moves to another part of the house (say, the kitchen) from their initial position, a shot would be used, and written like:

Int. XYZ’s House – Kitchen — Day

What is the Proper Format of a Screenplay?

This is the standard format for a screenplay (if you’re using a screenplay format template, make sure it follows these rules):

- Typeface – 12-point Courier font

- Margins – left margin 1.5 inch, right margin 1 inch (or anywhere between 0.5 inches and 1.25 inches), ragged, and 1 inch for top and bottom margins.

- Page Numbering – this should be done in the top right corner of the pages (flush-right) and should be half-inch from the top. Every page number should have a period at the end. Furthermore, don’t count the title page as the first page. Start numbering from the 3rd page (which comes after the title page and the first page of the screenplay), and also, mark it as page number two.

- Placement of Dialogue – dialogues should be placed 2.5 inches from the left side of the page (and 1.5 from margin).

- Placement of Dialogue Speaker Names – these should be in all caps and placed 3.7 inches from the left side of the page (and 2.2 inches from margin)

- Parenthetical/Wrylies Placement – parentheticals should be placed 3.1 inches from the left side of the page and 1.6 inches from margin.

- Lines per Page – there should be around 55 lines per page (not counting the page numbers). It doesn’t matter if you’re writing/printing on A4, A3, or any other type of paper.

Indents and numbering aside, another rule of thumb is to have only 1 minute of screen time per page.

How Screenplay is Written

As you can see above, screenwriting isn’t exactly a walk in the park.

But before you worry about formatting, you need to write an actual script and give some form of shape to your story.

Here is a step-by-step process (or best-practices in order, if you will):

1. Prepare Your Logline

This is a synopsis of the entire story or the summary of your plot.

The goal of a logline is to develop interest. It’s the first thing that potential producers will see, so make it count.

2. Create Your Plot

The next step is to actually work on your plot.

This will include what the story is about and its direction. Furthermore, it will include descriptions of all the main and supporting characters involved.

There’s no one right way to do this – you can type it up as a list on a Microsoft Word document, use post-it notes, or just jot everything down on a notepad.

3. Write an Outline for the Screenplay

Using your plot as a guide, start preparing an outline for your screenplay.

Make your outline as detailed as possible. You may include special notes throughout the whole thing if you want, but don’t worry about the formatting elements just yet.

4. Start Writing Your Screenplay

This is where the real work begins.

There’s no magic formula, software, or shortcut to prepare the initial, unformatted draft of your screenplay.

Just cut out distractions, seek inspiration, and remember to stick with the plot.

Furthermore, remember not to format your screenplay as you write. This will stifle your creativity.

5. Format Your Screenplay (with a Screenplay Format Template)

Once you’re done preparing the first draft, it’s time to start formatting it.

If you’re writing a short video or film script that’s only a few pages long, you might be able to do it manually in an hour or two.

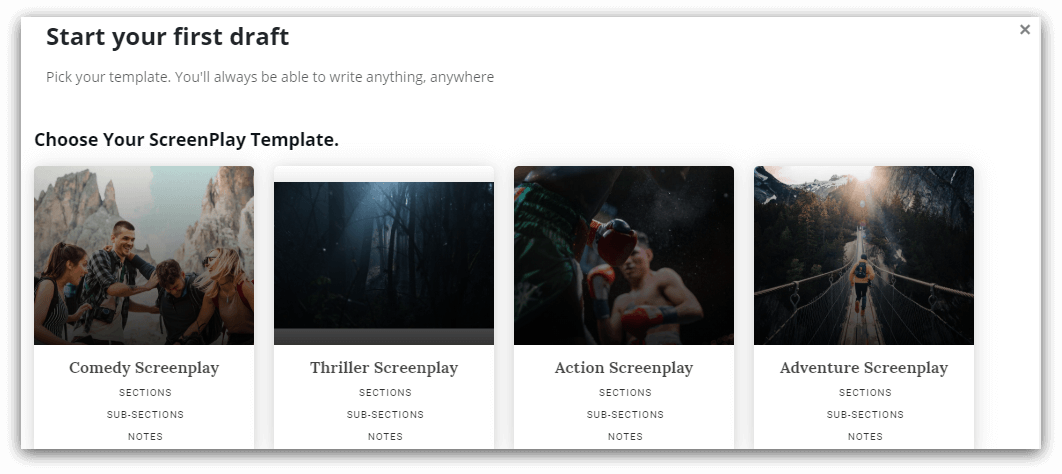

But with a screenplay that’s hundreds of pages long, it’s best to take help from a screenwriting software such as Squibler (which is also one of the leading screenwriting software currently in the market).

Not only will it save you a lot of time, but will also ensure that you don’t make any formatting errors.

With its different screenplay templates/script templates (for different genres), you can create a perfectly-formatted piece in no time.

You can start a 14-day free trial, get access to a screenplay format template, and take the software out for a test-run.

6. Edit, Edit, and Edit

After formatting everything, all you have to do is edit your screenplay.

Depending on how long your screenplay is (and how big of a perfectionist you are), this can be a time-consuming process.

Wrapping it Up

Is writing and formatting a screenplay hard?

It definitely is, especially if you’re preparing something for the first time.

Sure – we’re lucky to be alive during times when one of us can simply download a screenplay format template and cut down the time it takes to prepare a draft.

But no software can automate the creativity, thought process, or the subtlety behind an important scene (at least not yet).